There was a time when environmentalism wasn’t a corporate slogan, when rebellion wasn’t a brand, and when the act of defending the land meant getting your hands dirty, literally. Edward Abbey’s The Monkey Wrench Gang, published in 1975, was a Molotov cocktail hurled at the encroaching machinery of industrial destruction, a manifesto wrapped in novel form, a call to action in the shape of an anarchic fever dream. It’s easy to dismiss it as just another piece of radical fiction, a dusty relic of teh counterculture, but that would be missing the point entirely. The book is more than its plot. It’s an idea—one that, in the forty-nine years since its publication, has become both more urgent and, paradoxically, more impotent.

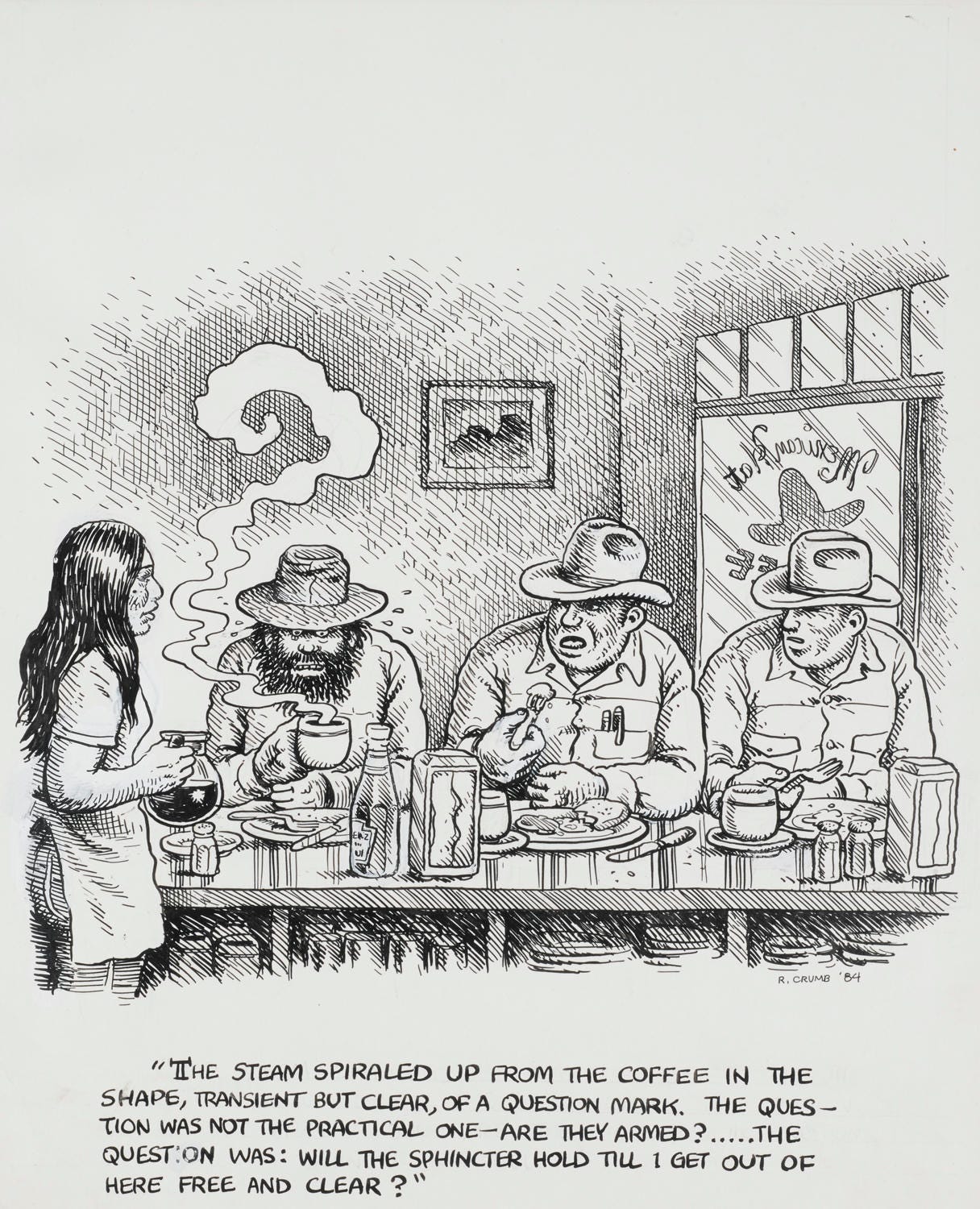

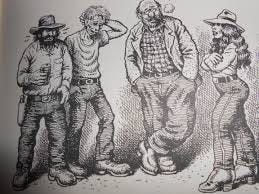

Let’s start with the premise. Four outcasts—a burned-out surgeon, an ex-Green Beret, a Mormon river rat, and a feminist revolutionary—band together to sabotage the unchecked spread of industrialization in the American Southwest. Their weapons are fire, dynamite, and ingenuity. Their enemies are bulldozers, railroads, dam projects, and the cancerous expansion of highways. Their goal is simple: to stop progress, or at least what the suits and bureaucrats call progress. Because “progress” in Abbey’s world—and in ours—means erasure. It means pipelines cutting through sacred land, it means the drowning of canyons for the sake of electrical grids, it means the systematic destruction of wilderness in the name of convenience, commerce, and control.

At its core, The Monkey Wrench Gang is about defiance, about drawing a line in the red rock and saying, No further. It’s an angry book, written by a man who saw what was coming and understood that polite activism wouldn’t be enough. Abbey’s vision of the Southwest—the sprawling emptiness, the raw, untamed beauty—was already under siege in the seventies. Today, it’s a battlefield long since overrun. The highways were built. The dams were finished. The tourism industry, once a creeping parasite, has become the host organism itself.

And that brings us to the present. Because the real question is: What does The Monkey Wrench Gang mean in an era where rebellion is an aesthetic? Where the kind of destruction Abbey’s characters fought against is now sold as an adventure package on Instagram? Where “wilderness” is something you reserve six months in advance through an app? Abbey’s characters dynamited bridges to halt the tide of civilization. Today, influencers in $500 Patagonia jackets fly in on private jets to snap selfies in places that used to mean something.

But then, sometimes, you don’t need to go searching for destruction, it finds you.

I had a tree. A single, twisted, gnarled juniper that I thought of as mine, though of course, it belonged to no one. It stood on a sliver of public land at the edge of Canyonlands, a wind-shaped, sun-scorched survivor in a landscape that had no business supporting it. Every time I passed, I’d stop. Lean against it. Run my fingers across its bark, smell the resin, listen to the wind cutting through its branches, carrying the scent of cedar and petrichor. It was a quiet monument to endurance, to patience, to something larger than time.

And then one day, it was gone. Who knows how old it was, the junipers in the area have been dated to be anywhere from 350-700 years old.

Cut down. Chainsawed, clean through at the base, the trunk left to rot in the dust. No one had built anything in its place, maybe a fire. No logical explanation beyond the raw, idiotic cruelty of someone deciding that it needed to be used. It was just gone. A small, unnecessary act of violence against something irreplaceable.

That’s the thing about loss. It isn’t always spectacular. Sometimes it’s just a single tree, on the edge of nowhere, taken down for no reason at all.

It’s almost funny, in a way. The original monkey wrenchers—if they existed today—would be labeled eco-terrorists, but their enemies wouldn’t be teh dam-builders and highway crews. No, their true adversaries would be the corporate greenwashers, the billionaires funding carbon offsets while buying oceanfront property, the brands selling “sustainability” while churning out endless disposable garbage.

Abbey wasn’t naive. He understood that civilization, once it reached a certain momentum, was nearly impossible to stop. But what he underestimated was how thoroughly rebellion itself would be commodified. The industrialists he railed against were at least honest in their greed. Today’s villains wear the costume of progressivism. They don’t build dams, they “offset” them. They don’t rip through the desert with bulldozers; they pave the trails, add parking lots, and install WiFi so that every curated moment of “wilderness” can be instantly uploaded and optimized for engagement.

The question that The Monkey Wrench Gang forces us to ask, nearly fifty years later, is a bleak one: Is there even a fight left to fight?

Because here’s the thing, Abbey’s gang had an advantage. Their enemy was tangible. They could see the bulldozers, the concrete mixers, the men in hard hats laying the foundations of the future they despised. But today’s machines of destruction aren’t so obvious. They exist in boardrooms and on balance sheets, in policy meetings and investment portfolios. The true wrecking crews don’t drive Caterpillars; they move ones and zeroes, erasing forests with a signature on a development deal, selling access to nature while pretending to protect it.

And the so-called resistance? The ones who claim to carry the torch of Abbey’s legacy? They’re too busy arguing about language, too busy signaling their virtues in curated posts, too busy buying limited-edition outdoor gear made from 80% recycled plastic. Real resistance isn’t sexy. It isn’t marketable. It isn’t safe.

Abbey wrote about men and women who risked prison to stop the destruction of the wild. Today, “environmental activism” means donating to a non-profit that prints its annual reports on FSC-certified paper. It means attending a gala, sipping sustainably sourced wine, and feeling good about yourself while the last wild places disappear under a wave of strategic development.

But maybe I’m being too cynical. Maybe the spirit of The Monkey Wrench Gang isn’t entirely dead—just buried under layers of irony and self-indulgence, waiting for the right moment to claw its way back to the surface. Because the truth is, the world Abbey wrote about—the vast, open, untamed desert—is still out there. Wounded, sure. Scarred and subdivided and fenced-off, but still there. And the question remains: Does anyone have the guts to fight for it anymore? Not with hashtags. Not with think pieces. But with action. With the kind of reckless, desperate, and inconvenient resistance that Abbey knew was the only thing that ever really worked.

Support your local bookstore, but if you’re lazy, here’s a link: The Monkey Wrench Gang

"selling access to nature while pretending to protect it". Beautifully written and painfully accurate.

Bud! What a great piece! Thanks for writing I will pass this along 🙏